When I meet new people or apply to a job, I often end up telling my life’s story. I often get told that it is inspiring to hear because I chose an unconventional and courageous path. I don’t mind telling the story over and over again, but at some point I decided to write it all down and share it publicly so that everyone may benefit from these experiences and insights. If you’re looking for a summary, go to my Twitter or LinkedIn. This is the full story. Very, very, very few people will enjoy reading it. If you are one of them, I am doing it, first and foremost, for you. Second, I am doing it because some day more people might care and then I don’t want someone else to attempt to make sense of my life. And third, I do it for myself because I enjoy structuring, expressing and debating my thoughts. Writing them down makes that easier.

Origins

My Name is Achill – my friends pronounce it in many different ways and you are entirely free to choose your own. The name comes from Achilles/Achilleus/Ἀχιλλεύς[Akhilleús], the hero of that famous Greek epic. For some mysterious reason, there is also an Indian version of that name – it actually sounds too similar for it to be a coincidence: Akhil – and that is what my maternal as well as my spiritual family call me. My mother is from the mountains enclosing the Kashmir valley in northern India and my father is from a German family that was forced to leave Lower Silesia during the second world war. Their marriage was arranged through an ashram where they practiced the same meditation and followed the spiritual teachings of the same Guru in India. I grew up with one lovely sister in West-Berlin of the 1990s. No techno for us, though. I didn’t touch a drop of alcohol throughout my teens because my parents were very strict and concerned with keeping us out of the mainstream party culture. In its place they imbibed a strong spiritual foundation by frequently taking us to the meditation gatherings of our ashram. Thanks to that meditation, I was able to focus and think clearly which certainly helped with exams. My parents also made it a priority to pass on their intellectual curiosity by taking me and my sister to historical places and cultural learning centers on virtually every holiday. However, I was rather shy and socially insecure during this time, which probably had to do with acne and the low self-esteem it causes. Being a social misfit forced me to build my own mental models of the world. It also led me to develop a strong curiosity, fascination and acceptance for other minority subcultures and their unconventional ways of living life.

School

As a consequence of all this, I was very good at school. I graduated as the valedictorian of my class. But I was unable to pinpoint a true passion among the options that were laid out in front of me. Thus, I spent a year traveling, working at a supermarket, learning languages and doing more or less fake internships to see the world and find out what role I wanted to play in it. After visits to Congo-Brazzaville and India I decided that I wanted to fight poverty and the global wealth gap. I discovered Economics – a subject that had not really been recognized at German schools – as the academic discipline which had the right tools for my chosen pursuit and combined many of my innate tendencies. But I also wanted to nurture my wider interests and fascination with the ‘big picture’, so I enrolled in a combined Bachelors degree program at a small Bavarian town called Bayreuth (the only place in Germany that offered it): Philosophy & Economics. It was a bit of a culture shock, to see the “real Germany”. During the first year, I lived in the house of a duelling fraternity because I had no idea what a duelling fraternity was and I liked the low rent. I was still not drinking and meditating a lot and excelling at academics. I got increasingly interested in macroeconomics and got a position as a teaching assistant at the university for that subject. I also worked as a teaching assistant for formal logic. Thanks to those accomplishments, I got the opportunity to spend my last year at college as a visiting student at Harvard University. I had learned from a brilliant senior (who had gone to Columbia for his third year) that this was possible and that one could get it paid for by various scholarship programs. Thanks Hannes, dad, DAAD, Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes and Stiftung der deutschen Wirtschaft for making it possible!

Learning from some of the world’s leading researchers, I built a solid foundation in formal economics, applied mathematics and econometric methods. I also got in serious contact with coding for the first time, because I particularly enjoyed analyzing data sets and identifying causal links. In my Bachelors thesis I investigated a question in economic geography: How does being close to a country’s border affect an area’s economic activity? [Link to thesis] In lack of granular GDP data I used satellite images of light density and turned them into STATA data sets with the help of GIS software.

Already during this time I also developed an obsession with observing social behavior, art and architecture. I was particularly interested in exploring ways for strangers to communicate with each other, because I always felt a painfully depressing and boring vibe in urban public space. I shared an apartment with Thomas Clark who is a landscape architect and photographer and became another lifelong friend to me. Together we started the Boston Social Box, a series of experiments designed to explore the possibilities of interaction in the Boston T metro system. I started writing down ideas for how to turn this into a digital product, but it was all still more performative art than entrepreneurship. [insert link to first writing]

I quite enjoyed my work as an economist and started working part-time as a research assistant on the empirical research projects of my favorite professors at Harvard: Nathan Nunn and Alberto Alesina. This led me to my absolute dream job right after college. I had wanted to continue doing academic research, but I was also ripe for another adventure and looking for a way to reconnect with my South-Asian roots. The Harvard career center had the perfect solution ready for me the moment I entered. I thank them to this day: They suggested I apply at JPAL, an economic research institute that had recently been founded at MIT down the street from Harvard. The principal researchers of JPAL had gained the reputation of being the most rigorous, no-nonsense people in the development industry. After a series of interviews it became clear that they considered me a good fit and I got sent to work on a project led by the founding directors Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee in the poorest and roughest part of India: Rural West Bihar.

My First Real Job

For the following two years I was responsible for implementing a large scale randomized control trial that aimed to determine the long-term economic impact of a health policy [insert link to paper]. A lot of people in India suffer from iron deficiency anemia so the idea was to add iron to salt – similar to how we already add iodine. My job, along with two other team members’, was to make this new super-salt available in 200 randomly selected villages while keeping it out of 200 other villages in the same area. By comparing the health of people in those villages before and after the intervention, we would find out how it impacted their physical health, cognitive ability and economic productivity. My particular responsibility was to digitize, clean and analyze the vast amounts of survey data that was coming in on paper response sheets from the field. At times the office I managed had 20 employees typing away (and occasionally binging on whisky under the table at the same time).

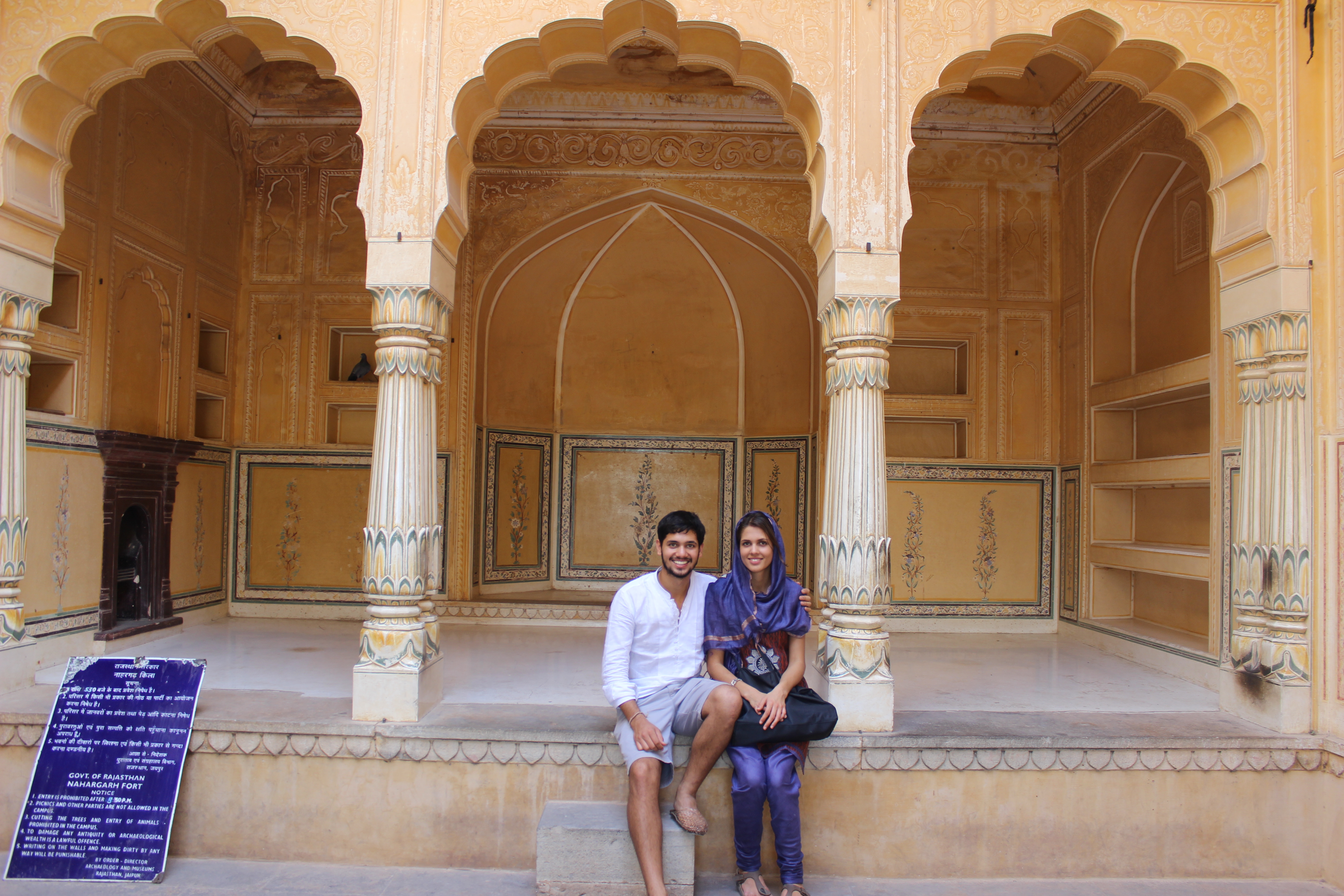

Having the responsibility to manage big teams in an alien land under adverse environmental conditions was a beautiful adventure that helped me grow as a leader. I got the job done and moved on to other projects by the same researchers in more pleasant parts of India: The second year I lived in the old red city of Jaipur. On the weekends I would tour Rajasthan on a Royal Enfield motorbike and frequently travel to Ahmedabad, Delhi or Goa with a new kindred spirit, Nikhil Wilmink, and other wonderful people I met. Something else happened here: Far away from home and set free by the randomness of it all, I was convinced by a very persuasive new friend to try a few glasses of rum before going to a Delhi rooftop party. That night I discovered a deeply social, confident and funny person inside of me. For the first time, I experienced what makes partying and socializing enjoyable. I started liking myself more under the influence of alcohol, made a lot of drunken new friends and entered my first romantic relationship at the age of 22.

The academic dream

After 2 years in India, I had had enough and wanted to come back to the developed world. Luckily, when you do good work for a professor, this can help you skip the line for graduate school and get admitted without a master’s degree. This seemed like the coolest thing to do at the time. I got accepted at Yale for the Economics PhD program with a generous stipend. I moved to New Haven and enjoyed the perks of graduate student life at an Ivy league school. While others are paying or even taking debts to access the facilities and learning resources of this institution, as a PhD student you get paid – and an amount that felt like a proper wage already. On the way to your PhD you get a Masters degree, too! I knew I wouldn’t necessarily stick around for the entire 5-6 years program, but it all seemed like a very good deal, especially once I was through with the daunting exams at the end of the first year.

At Yale, I met my third fantastic friend: Fabian Eckert. He was also German, in the same PhD class and definitely the better student. He pulled me through the heavy coursework on more than one occasion. But we also understood each other on a fundamental personal level and started celebrating wonderfully awkward experiences together in the foreign world of suburban America. We moved together and founded the legendary Konsulat on Dwight Street – a house filled with Germans who were fundamentally at odds with American student culture (and completely bewildered by American non-student culture). We were fortunate to have a two-story garage in the backyard that had been used by architects to build boats at some point. This became the venue for unforgettable parties, art events and other extravaganzas.

Getting off-track

Around this time my doubts about pursuing academics grew. Thanks to my first experiences with Marijuana and LSD, I discovered an immense creative drive in me, that led me to make documentary films. I started taking sculpture and documentary film classes on the side and used every summer break to travel to a place that fascinated me and capture a story I would find there.

Camera equipment was getting affordable and small enough for me – a complete amateur – to go out and capture a real story as it was unfolding in front of my eyes. Some of these stories seemed just as exciting, clear-sighted and unbelievable as a fiction movie. What also excited me about storytelling was the therapeutic effect it had on me. I had started to think very deeply about fundamental questions of life and had even gotten a bit depressed briefly after realizing how fucked up everything was on an existential level. When making a film, I would choose a question that kept me thinking or a problem that bothered me and find a person who was facing challenges related to that same problem. After going through an issue in this way, I felt that it got resolved and I could move on. That is how I view good documentary film: It does not pretend to have a logical answer to the big questions in life. It just shows the incomprehensible magic, limitless beauty and poignant sadness of the world, opting to celebrate it instead of despairing over it.

My friends enjoyed watching these personal documents and encouraged me to keep making films. But at some point I had gone through all my “issues” and didn’t really feel drawn towards new film projects. I also realized that I would not want to depend on making art for a living. I could only do so as a pure form of expression without expecting or aiming for approval and recognition. And so I reanimated my entrepreneurial visions and started systematically writing down and testing different business ideas that had popped up over the years.

A new start

The signs of the universe kept leading me away from academics and hinted that my path was in entrepreneurship and the creative arts. I dropped out of the PhD and moved back to Berlin. Transitioning from the academic ivory tower into the wild market economy, I took various jobs – as a construction worker on a house renovation, as a warehouseman at a film festival, and eventually as a brand strategist at a marketing agency called WAALD. At WAALD I could develop my business skills while at the same time continuing to express myself creatively (if coming up with advertisement slogans counts as creative). I was also able to pursue filmmaking by taking on clients who wanted a documentary film produced in order to improve their public image (for example, I planned and directed this series of portrait films for an association of German universities).

Back in Berlin, I was also surrounded by tech-savvy people, who could show me how to turn my ideas into digital products. One of these people was Simon Huesken, a true libertine digital nomad whom I had met while he was an undergraduate philosophy student at Harvard. I bought him lunch one day and told him about my persistent troubles with the social climate in public space. Even as a young adult working at a hip agency in Berlin-Kreuzberg – the universal center of coolness – I was not very happy with my social life: I would hang around mostly with the people I worked with. I didn’t want to spend every lunch break with these people when so many beautiful and interesting hipsters were going to eat at the same places every day. Meeting people outside of that bubble turned out difficult even as someone who had grown up and was at home in this city. So I convinced Simon to help me build a simple one-page Javascript web app, that allowed users to arrange spontaneous lunch breaks with strangers. We called it MeetXBerg. The idea was for it to become a platform where you could find compatible people nearby for spontaneous networking and socializing anywhere and any time. But we started in Kreuzberg, because that’s where I was. And in the beginning the only person one could actually meet using that app was me, because I was always available and responded to every request.

The site got shared in the local community and on other workplace’s slack channels and for a month or two I would get 2 lunches every week – with people I had never met! Every time I saw a signup in the database (that I hardly knew how to query) I got excited, looked up the person online and eagerly awaited the new encounter. Of course, the idea itself was the main topic of discussion at most of these lunch meetings and I realized that those other people had similar concerns about social life in the city. Many of these encounters led to enriching conversations or opened the doors to new knowledge and personal connections. This was the first time I consciously experienced the power of technology. The fact that I had created it and could possibly scale it up, making millions of people happy the same way, left a deep mark on me. I realized that building technology was the most promising way to create an impact and help improve life on earth. I turned away from filmmaking, economics and marketing as a profession and decided to pursue technology entrepreneurship once and for all.

On one of my business trips with the marketing agency (to Tbilisi, Georgia of all places) a guy who was staying in the same hotel told me that he had come to Tbilisi all the way from Estonia in order to attend a hackathon. I had only ever thought of hackathons as highly dubious and exclusive events for a group of people that I would never have anything to do with. But I had some time because I had booked a late return flight so I could see the city after the business meetings were over. He insisted that I should use the opportunity to come to the hackathon and pitch my idea on stage. A few hours later I found myself with a bunch of Georgian programmers and designers who were enthusiastic about the vision of MeetXBerg and started working through the night to make that vision come true. After this experience I got addicted to hackathons and went to every single one I could find. Around the 4th time, I adapted the same business idea for waiting airport passengers, because the hackathon had been sponsored by a major European airport association.They liked what we built and I won the hackathon together with a bunch of strangers I had picked up at the event. A little bit of prize money, 3 months of office space at the startup incubator of Deutsche Telekom and a randomly assembled team that included some people who seemed to know what they were talking about, were enough to make me quit my job and turn my full attention (and all my savings) to the pursuit of my own entrepreneurial dream.

Humble beginnings

The team fell apart after it became clear that I was the only one who was actually serious about the project. I found other people (in times of desperation with unconventional means) but no one would commit for long. I was frustrated because I depended on technical people to replace my utter ignorance but at the same time the pressure was too big for me to be able to sit down and start learning it myself. I had started to fix things on my own when I couldn’t get anyone else to do it but learning to code still seemed like an insurmountable challenge. I didn’t think I would be able to catch up on it at this late stage of my life. I found a new co-founder at a startup conference and over several iterations we built an MVP and tested it at the airports. But they were not impressed. The money ran out and I was already on the brink of throwing the towel, when I discovered steemit and realized that blockchain is likely to disrupt not just finance but also social media. At the same time, a young Italian business student pulled me aside after a pitch contest I had won and ended up joining the project. With the blockchain hype of 2017, we regained momentum and secured a 6-month funding program financed by the European Union and German government. This allowed us to hire a mechanical engineer as a third team member. He had just started learning web development, so could pass as a CTO.

We changed the product to become a token curated ranking of blockchain experts in Berlin. Apart from that we didn’t get much product development done in those 6 months but finally I could dive into the code and concentrate on learning everything I needed to not be dependent on other people when bringing a product to life. I developed a passion for learning with udemy tutorials, especially from a guy named Maximilian Schwarzmueller. And I discovered the depths and multiple facets of blockchain technology, which perfectly combined my background in philosophy and economics with my newly found interest in coding. I naturally felt drawn to reading white papers and spent many months going through token economies and learning smart contracts engineering with Solidity.

I am a developer now?!

There was a point where I realized that with the help of udemy and StackExchange I could basically solve every programming problem and learn everything I always thought outside of my domain. At that point I got hooked and started spending every morning, while still eating breakfast, with a tutorial or Harvard CS50 lecture on YouTube to learn something new and apply it to my project. I love the internet for making highly specific and complex information available at almost no cost.

In the tech community, this potential power of the internet is harnessed best because it meets with a relentless spirit of collaboration. I have been extremely impressed and motivated by the support, care and attention people give each other in this community. Once you are past the point where everything intimidates you, you realize that everyone is constantly learning and happy to help each other, so that the ecosystem can progress as a whole. Every difficult concept can be broken down into baby English – and a good explanation should be using baby English. It was only with the help and advice and guidance from people I had met at hackathons and meetups, who explained things to me in baby English, that I figured out what exactly I needed to learn and realized that I could learn it. Then it was just a matter of time and practice till I got to a point where I could make a lot of baby steps in my head without thinking.

If you want to teach yourself software development, my key advice is this: Find a project that feels like it is worth spending a lot of time on. Do whatever is needed to complete it and let the requirements of that project guide you through the material. On the way you will get the required practice and find a niche where you can touch the current frontier and connect with the tech community working on this frontier. For me this niche was the decentralized attention economy and blockchain-based social media. I entered the discourse around this topic and built relationships with the experts in this field. Within a few months I had become an expert myself. I started writing about my work, presenting it at conferences and bringing projects and people together through a new meetup group in Berlin.

My tech products didn’t take off and basically no one cared. But whenever I started building something I genuinely believed that it could be very valuable and therefore would not give up until a basic version of it was in existence. When it was there and I had shown it to the community and people still didn’t care, I would admit that I was maybe being crazy and turn to the next idea.

Hitting rock bottom

But there is only so much time you can spend without an income. None of my projects quite hit the nerve of the market and I was unable to secure an investment after the first funding ran out. I had decided not to accept more support from my family. And so I was faced with acute poverty. I kinda liked it though:

The stress of being broke helped me get the best out of myself: I finally managed to build a disciplined daily routine and get up early in the mornings. For the first time in my life I knew that I had to give it everything I had got. I revamped my meditation practice. When you don’t have money and time for anything fancy, you learn to be happy with the simple and sustainable pleasures that come from within. I cut out parties, alcohol and drugs from my life because they cost the most time and money but did not help at all with the challenges I was facing. I got as fit as I had never been before thanks to daily workouts with my gym buddy Duc. I started keeping my phone off during the day and with all notifications disabled at all times (Deep Work is a book I recommend anyone who is trying to develop more focus). When there is no one to tell you what to do and no one to really care (except your exceedingly impatient family who are wondering why their smart grown-up son can’t afford to buy curtains) there is only one thing to make you get your shit together: The fear of failure.

I gave it my best and it still wasn’t enough to be able to continue as a full-time entrepreneur. This was to be expected as the most likely outcome but nevertheless it made me a bit sad. Looking back, I never regret having gone through this experience and this has two reasons:

First, my projects were always a bit weird and I only ever intended them as an offering for a special group of people: They were something I would have wanted to leave in the world because I thought if they were to be created it would have to be me who creates them. I wanted to build something for people who appreciate similar things as I do and never expected the main stream to like it. It turned out there are not enough of those people for my work to find a sustaining audience right away. This is a certainty I could only arrive at by trying. I am glad to be able to say for sure that the products I envisioned are not in high demand. Nevertheless, I will keep offering and refining my gift. Having learned from my mistakes, I am now better able to find the intersection of what I am passionate about and what the world wants.

Second, starting a company was the best way for me to learn about entrepreneurship, business and technology. It felt somewhat like a university course, complete with modules, submission deadlines, teachers and mentors. It taught me self-discipline, project management, presentation skills, lean startup methods, blockchain technology, and turned me into a full-stack software developer. The big difference to a university degree is that there is no one structuring the material for you or motivating you to do the work, except for that existential drive to survive as an independent entrepreneur. Your life and freedom are on the line. If you have a high risk tolerance, love to think independently and need challenges to get the best out of yourself, I can highly recommend this path.

No endings in life

Now, I am using the skills I have built in my own projects to help existing organizations. It was not difficult to find other projects that are aligned with my personal mission and interests enough for me to dedicate my time to them and feel honored to be able to contribute to them. Thus, I first joined Relevant, a decentralized attention network that I had been following closely since it was similar to steemit – the blogging platform that had originally gotten me into blockchain. I had made some open source contributions and jumped on the opportunity when founder Slava Balasanov asked me to write the smart contract code for the Relevant token economy including a complex and unique inflation mechanism. More recently I started working at Honeypot, a jobs platform that is on its way to become the world’s biggest support community for tech professionals. I am enthusiastic to embark on this new chapter because it allows me to combine my entrepreneurial experience with my software skills to develop new products that serve the tech community at large. I am almost 30 now, but it still feels like I am just getting started.

I hope you enjoyed the story of my life – thank you for your attention!

I also recorded a podcast with Crispin Scholz on his show With The Right People that recounts many of the episodes from above in more detail.